Blog

BEING A TEENAGER

About 700 years ago in medieval England, the age boundary between adolescence and adulthood as we accept it today was defined. At that time, the advances in iron smithing and military technology caused the armour and weaponry that most soldiers wore to battle to be sturdier and more resistant to damage than before. However, it was noticed that many of the younger soldiers were struggling: the heavier armour was simply too heavy for their frames, and they could not keep up with their older counterparts. As a result, the English redefined who was an (army-worthy) adult by changing the classification criteria from 15 to 21-years-old. To this day many countries regard the age of 21 as the official gateway into adulthood.

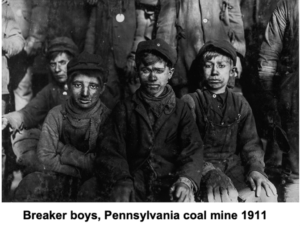

Being labelled a ‘teenager’ is, however, a relatively new societal phenomenon. In fact, the word only first appeared in print in a magazine article 1941 as a way of describing the

distinct stage of development between 13 and 19-years-old. In previous times, children

were considered to be an economic resource capable of most kinds of work, first on farms and then later in the industrial revolution, and as such were seen as mini-adults.

It was only in the 20th century that adolescence became recognised as a distinct developmental phase.

Today, we have a much greater understanding of what it means to be an adult than we did seven centuries prior, and much of this is based on knowledge about the brain. The teenage years are generally regarded as both difficult and memorable – a time of emotional ups and downs, and of new experiences that are often associated with risk-taking. Many a parent has lamented these years and the associated moods, unpredictability, and push for independence. What’s to blame? It’s commonly accepted that the unholy brew of hormonal and physical changes happening during adolescence, within a social context where peer acceptance is paramount – produces some of the best and worst moments in person’s life.

AN ADOLESCENT BRAIN UNDER THE MICROSCOPE

Less commonly known is the role of the brain in all of this, and exactly what goes on in the brains of teenagers. It’s not so much as what is happening in the teenage brain, but what is not. We know that teenagers can be impatient, passionate, rebellious, anxious, and highly prone to both addiction and peer pressure, but what is it about the brain-based biology that causes these things? Succinctly stated, it’s because of the varying rates of development of the different brain bits.

Of all the organs in the body, the brain is the most incomplete at birth. As it develops – and very slowly at that – two important things happen: it increases in size and the internal wiring changes. The brain is made up of grey matter, which comprises the neurons that are responsible for thought, perception,

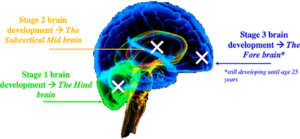

It also helps our understanding of the adolescent brain to know that, when developing, the brain wires itself starting from the back (base of back of the neck) and progressing to the front (forehead area). What this means is that the frontal lobe, the part of the brain responsible for judgement, insight, impulse control,

Delayed Pre-frontal Pruning

A critical factor in the development of the teenage brain is delayed prefrontal pruning. What is “delayed prefrontal pruning”? To answer this, we need to understand a bit about how the brain works. At birth, babies’ brains have 80% of the neurons (brain cells) that they will have in adulthood. By early adolescence, teenagers have even more than they will in adulthood. This might seem counterintuitive, but it becomes clearer if we understand that greater intelligence does not have to do with a bigger, or ‘fuller’ brain; it has to do with a more efficient one.

While children and adolescents might have more than enough brain cells, many of the connections (neuronal pathways) between them are unnecessary, and these useless connections make it more difficult for the brain to

Compared to the rest of the brain, the parts right at the front that deal with cognition, emotional regulation, and higher-order thinking (critical thinking, problem solving) – the prefrontal cortex – are the last to be pruned. That’s why younger people are capable of critical thinking, but it’s more time consuming and less efficient: those neuronal networks still have plenty of clutter. So, what happens while those parts are still developing? While they do indeed work, they either don’t work as well, or other parts of the brain take up some of their tasks instead. This explains why, for example, teenagers tend to be so emotional – the rational part of the brain isn’t fully functional yet, and the emotional parts (limbic system) have a greater extent of control.

Stand-in Brain Bits

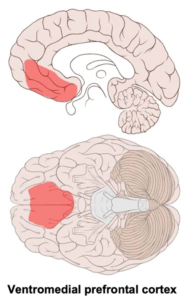

Now things get a bit more technical. From the afore explanation, we can see that, when it comes to calming down from emotional distress, adolescents and adults rely on different parts of their brains. When a normal, mature adult experiences something

Now let’s look at this same scenario, but from a teenager’s perspective. Again, the limbic system will activate, causing them to feel distress. However, compared to adults, the limbic system fires considerably more forcefully, and so they feel the upset more strongly or intensely. Compounding this is that a different part of the brain, called the ventral striatum, is called upon to assist in dampening the emotional response. The ventral striatum is not nearly as good as the vmPFC at quelling emotions because its usual job is to analyse risks. Calming a teenager and bringing rationality to the situation is only its part-time job, which it does while the prefrontal cortex is still developing. Thus, while a teenager does use their prefrontal cortex and its rationalising abilities, the cognitive load (demand) is “shared” with other parts of the brain to make up for its underdevelopment. This ultimately causes teens to experience emotions far more intensely and then be much worse at regulating them. For teenagers things can be super awesome and amazing or absolutely the end of the world, the latter especially so when rejection or hurt is involved.

ADOLESCENT BEHAVIOUR

It is easy to deduce from the explanation of the teenage brain why they tend to be highly reactive and unpredictable in their emotions. But what about other characteristic behaviours?

Risk-taking

The lack of inhibition or reserve when it comes to intense emotions also helps explain why teenagers often engage in high-risk activities like promiscuous sexual behaviour, substance abuse (drugs, alcohol, cigarettes), preventable injury, and violence. The reason has partly to do with their brains’ reward systems. The reward system does exactly what you’d expect it to: when we do something that makes us feel good, part of the reward system called the ventral tegmental area (VTA) releases lots of dopamine, a neurochemical that makes us want to do that action again. Dopamine is commonly known as the feel-good hormone or chemical and the good feeling people get is called a dopamine rush[1]. Contrary to popular belief, dopamine doesn’t actually make us feel good; it conditions our actions, causing us to want to do that same thing again so that we experience that rush.

When neuroscientists compared how the brains of children, teens, and adults responded to rewards, they noticed that teenagers – as expected – released far more dopamine than any other age group. Even medium rewards made teenagers feel better than the largest rewards given to children and adults. They also noticed something else that was interesting, which adds a caveat to this finding: when teens were given small rewards, dopamine amounts decreased. In other words, teens favour a go-big-or-go-home approach: if something motivates them largely, they’ll seek it out with vigour. If it doesn’t, they’ll elect to avoid it, even if it still rewards them.

Many dopamine rush-seeking activities are relatively harmless e.g., eating another piece of chocolate. But for teenagers, often these low-key actions or activities aren’t enough – they seek the intense feeling of reward. This (and poor vmPFC judgement ability) is why teens will do things that are more risky i.e., the rewards are higher. It’s also why adolescents are particularly vulnerable to addiction: taking part in addiction-related behaviours offers intense rushes at a time when the

Peer Pressure and Conformity

Another important aspect of adolescent development is peer pressure. Because teens are grappling with their identities and who they are in the world, they are particularly susceptible and vulnerable to peer pressure. While they seek to define themselves and develop self-confidence, they also seek validation and desire acceptance from their peers by ‘fitting in’. The increased limbic activity in a teen’s brain strengthens / heightens the need to belong.

Some believe that peer pressure is the single most formative factor in behaviour in the adolescent years. How susceptible are teens? In one study, adults playing a video game with two peers didn’t affect risk-taking decision-making, but in the same scenario with teens, the number of risks taken tripled. The presence of peers influences behaviour. This can be a good thing if it’s positive peer pressure but can go horribly wrong if it’s bad.

Idealism

It’s not all doom and gloom, however. The intensity of emotions felt by a teenager can be a positive thing when tied to a force for good. In early adolescence the brain’s computational capacity increases dramatically, ushering in the ability for abstract thought about the world that was absent in childhood. As we now know, teens rely more on emotional reactions than on logical reasoning in decision-making and responses. This can translate into an emotion-driven, passionate, and “idealistic” response to how they want the world, or merely their direct environment, to be. Often, they idealistically seek social change, which is why intentions about overthrowing oppressive regimes and saving the world, as well as initiatives to improve the planet, are commonplace. Some names you might recognise as influential teenage activists are Joan of Arc (led the French army against England), Malala Yousafzai (women’s and girl’s education), and Greta Thunberg (climate change activist).