Blog

The Happiness Pie

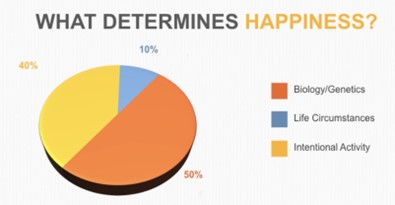

The Happiness Pie, a well-known albeit a bit simplistic model, is a good place to start if we want to examine what influences our ability to be happy (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005; Brown & Rohrer, 2019).

According to the Happiness Pie, approximately 50% of how happy we are is a product of our genetic inheritance. Some people are inherently more optimistic and happier than others – they see beauty and opportunity where others focus on problems and dangers. Although personality tends to be stable throughout life, it is possible to change some dysfunctional thought processes by rewiring (metaphorically) neural network patterns. Cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) can assist in modifying a negative outlook by reframing selfcriticism and negative thoughts (Davidson & McEwen, 2012). There is not, however, a one-size-fits-all approach because people have different coping styles that affect the way they deal with things e.g., the defensive pessimism that some anxious people feel can be harnessed to help them get things done, which in turn makes them happier (if it’s not broken, don’t fix it).

selfcriticism and negative thoughts (Davidson & McEwen, 2012). There is not, however, a one-size-fits-all approach because people have different coping styles that affect the way they deal with things e.g., the defensive pessimism that some anxious people feel can be harnessed to help them get things done, which in turn makes them happier (if it’s not broken, don’t fix it).

The Pie indicates that around 10% of factors that affect happiness relate to life circumstances such as where you were born, levels of wealth or poverty, educational resources, and cultural context. It’s generally very difficult to change these circumstances, which brings us to the remaining 40% i.e., intentional activity, where we have the power to effect positive change.

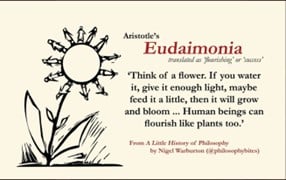

Decades of evidence-based research, including contributions from neuroscience, has shown that Aristotle was indeed correct when he proposed that there are two kinds of happiness, hedonic and eudaimonic. Both contribute to happiness in life, but in different ways. Daniel Kahneman, winner of the 2002 Nobel Peace Prize in economics, differentiated between momentary and fleeting happiness, and a long-term feeling of satisfaction / contentment, built over time by achieving goals and the kind of life you admire (Kahneman & Deaton, 2010). It’s happiness as an attitude (a function of how you choose to live life) versus happiness as an emotion (pleasure).

The Pie indicates that around 10% of factors that affect happiness relate to life circumstances such as where you were born, levels of wealth or poverty, educational resources, and cultural context. It’s generally very difficult to change these circumstances, which brings us to the remaining 40% i.e., intentional activity, where we have the power to effect positive change.

Decades of evidence-based research, including contributions from neuroscience, has shown that Aristotle was indeed correct when he proposed that there are two kinds of happiness, hedonic and eudaimonic. Both contribute to happiness in life, but in different ways. Daniel Kahneman, winner of the 2002 Nobel Peace Prize in economics, differentiated between momentary and fleeting happiness, and a long-term feeling of satisfaction / contentment, built over time by achieving goals and the kind of life you admire (Kahneman & Deaton, 2010). It’s happiness as an attitude (a function of how you choose to live life) versus happiness as an emotion (pleasure).

Hedonic Happiness

Hedonic happiness is all about the feel-good factor, about happiness as an emotion. It’s a transient feeling of joy, pleasure, enjoyment, or

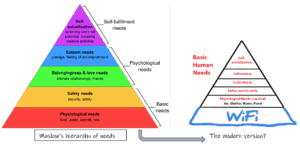

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

Not all desires, needs, or wants, are of equal import. Maslow, in his Theory of Motivation, proposed a hierarchy of needs. He wrote: “It is quite true that man lives by bread alone – when there is no bread. But what happens to man’s desires when there is plenty of bread and when his belly is chronically filled? … At once other (and “higher”) needs emerge and these, rather than the physiological hungers, dominate the organism. And when these in turn are satisfied, again new (and still “higher”) needs emerge and so on. This is what we mean by saying that the basic human needs are organized into a hierarchy of relative prepotency” (Maslow, 1943). According to his theory, people have a hierarchy of needs and once the very basic ones – those at the bottom of the pyramid – are satisfied, their needs progress further up the pyramid.

The Hedonic Treadmill

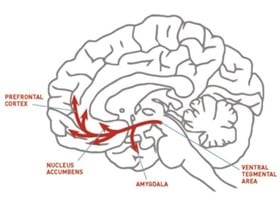

The seeking circuit is the default mode in the brain – we are always seeking. The advertising industry thrives because of this. It bombards us with messages about things that we should want and need, even if we don’t. So, we buy them, and feel happy. We buy them to enhance our status among our peers, or to keep up with the Joneses or Motsepes, but mostly we buy them because we think they’ll make us happy. And they usually do – for a short while. This is because, while happiness is an emotion felt in the here and now, it ultimately fades. Positive affect (emotion) and feelings of pleasure are fleeting. Then when it’s gone, we look for the next thing to buy that will release a surge of dopamine in the brain. And so the cycle continues. This is called hedonic adaptation or the hedonic treadmill.

People are remarkably good at adapting, so once a ‘want’ is satisfied and the dopamine surge has diminished, it takes something more or bigger to get the same dopamine high the next time around. The economic principle of the Law of Diminishing Returns applies; as investment in something increases, at a certain point the yields of that investment decline, even if the amount of investment stays the same. For example, by the time you buy your fifth Lamborghini, it’s unlikely

What this all means is that, after a certain point (when basic needs are satisfied), money generally does not bring proportionally more happiness. It’s good to experience the pleasures that money can buy, but they shouldn’t dictate your life. When efforts at happiness are tied to wealth, romance, or materialism, the joy will be transient. There are, however, exceptions. Cosmetic surgery is one of them – studies suggest that money spent on cosmetic surgery or enhancement results in longer-term happiness, probably because it is associated with increased self-esteem (Castle et al., 2002; Haas et al., 2008). Another three ways of spending that are good at converting money to happiness are; 1) money spent on others, 2) money spent on buying back leisure time to be with loved ones, and 3) money spent on experiences rather than material possessions. Experiences create memories and memories stay with us for much longer than a dopamine surge does, thereby extending the duration of happy feelings.

Eudaimonic Happiness

The other form of happiness is what Aristotle called eudaimonia and it’s about human flourishing. It’s not about seeking the dopamine surge, it’s about being in it for the long haul, about enduring happiness. In psychology terminology, it’s about positive cognitive appraisals of meaning and life satisfaction i.e., how you view your life and the meaning you attach to your activities, achievements and deeds in it. “Happiness without meaning characterizes a relatively shallow, self-absorbed or even selfish life, in which things go well, needs and desire are easily satisfied, and difficult or taxing entanglements are avoided“, said Viktor Frankl

You shouldn’t “pursue” happiness — you should “construct” or “create” it

It’s similar to achieving permanent weight loss i.e., it necessitates making some permanent changes and requires effort and commitment every single day (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005; Waldinger, 2015)

A quick note on suffering: It’s important to recognise and accept that being happy

Happiness is meaningless without sadness. Happiness is not the result of bouncing from one good thing to the next, but rather, achieving happiness typically involves times of considerable discomfort. Those who accept that a meaningful life encompasses what Hamlet called the ‘slings and arrows of outrageous fortune’ are better equipped to experience real happiness (Gilbert et al., 2012; Harris, 2008).

Relationships

Research suggests that strong personal relationships are the biggest single indicator for happiness in life, so it’s worth cultivating, enjoying, and where necessary healing, relationships with those around you. Studies consistently find that people who value money, fame, and image are less happy than those who value community and affiliation with others. The lyrics of Baz Luhrmann’s song Everybody’s Free (To Wear Sunscreen) advise that you “Get to know your parents, you never know when they’ll be gone for good. Be nice to your siblings; they are the best link to your past and the people most likely to stick with you in the future. Understand that friends come and go, but for the precious few you should hold on. Work hard to bridge the gaps in geography and lifestyle because the older you get, the more you need the people you knew when you were young.” The song has some really good lyrics and it’s worth taking 5:06 minutes of your time to listen to it: https://youtu.be/3FYlPEC8yb4.

Goals and achievement

Having goals is another indicator. People who strive for something are far happier than those who don’t have dreams or aspirations. Achieving goals make us happy whether they are big like a happy marriage, or small e.g., losing 2kgs. It’s not only achieving goals that make us happy – anticipating achieving something activates positive feelings and suppresses the negative. A state of anticipation is linked to a sense of possibility and hopefulness. One study showed that people reported that they often experience greater happiness planning for and anticipating a holiday than being on the holiday! However, goal setting and achievement comes with a caveat: if your motivations are superficial e.g., to boost your ego or keep up with the Joneses, then the resultant ‘happiness’ will be superficial too (Adams et al., 2009; Huron, 2008; Van Boven & Ashworth, 2007).

Satisficing

Satisficing is when you make a decision about something based on an acceptable or satisfactory outcome, not the maximal outcome – and then being content with that choice. Satisficing also helps in managing something called the Paradox of Choice, which is

Sparks of joy

Taking delight in the little things that happen throughout the day can cause a gear change in your neural

Kindness

Bringing small moments of joy to others is also a good source of energy to charge up your happiness powerbank. Specific parts of the cingulate cortex in the brain increase in activity only when we are being kind to someone else. Random acts of kindness – being kind to others, both friends or strangers – can trigger a cascade of positive effects within you by boosting feelings of confidence, optimism, being in control, and happiness. Kindness in itself has been linked to mood improvement, increases in self-esteem, empathy, and compassion, and a decrease in blood pressure and cortisol the stress hormone (Curry et al., 2018; Fredrickson et al., 2008; Hurley & Kwon, 2012; Lockwood et al., 2021).

Problem-solving versus overthinking

After cows swallow their food, it goes into one of the four chambers in their stomachs to ferment, only to be returned to the mouth again for more chewing. This is called rumination, and it comes from the Latin word ruminare, which means to chew again. Some people ruminate on their thoughts – they revisit

So it seems that happiness takes lots and lots of work. We need to actively focus on it and re-learn the childish joyousness of simply living and appreciating in the moment. In part III I will give a short description of what a happy person looks like.