Blog

Have you ever been around someone who was extremely emotional or upset? If so, you’re probably familiar with the phrase “Oh, stop being so hysterical!” Well, with that in mind, did you know that “stop being so hysterical” comes from a very long history of equating women’s emotions with madness and more specifically, hysteria?

The story started with the ancient Egyptians. Nearly 4,000 years ago, they decided that hysteria was caused by the random movement of the uterus within women’s bodies. The Egyptians’ northern neighbours, the Greeks, helped nurture the idea in their mythology where, according to the Argonaut Melampus, a woman’s madness/hysteria came from a lack of a sex life which caused her uterus to be poisoned by venomous ‘humours’ — a kind of liquid within the body.

Not to be upstaged by an imaginary being, Plato and Aristotle, after some considerable pondering – as Greek philosophers do – got together with Hippocrates, the “Father of Medicine”, and concurred that the affliction was, indeed, caused by a funky uterus. The treatment, these men suggested, was to have sex. By attributing hysteria to a lack of sex, a connection was created between female sexuality and hysteria that remained pervasive for hundreds of years afterwards.

During the Middle Ages, Hippocrates’s many ideas began to spread throughout Europe and along with it the notion that symptoms such as anxiety, shortness of breath, fainting, insomnia, fluid retention, heaviness in the abdomen, irritability, loss of appetite, sexually forward behaviour, and a “tendency to cause trouble for others”, i.e., hysteria, became synonymous with women and their “pesky” uteri. Christianity, too, got in on the action from the 13th century onwards and as a result, hysteria also became associated with sorcery — especially the devil and witchcraft.

In the 14th century, the Renaissance came to the rescue – albeit very, very slowly – by introducing the ideas of humanism, a reverence of education, and a reliance on science, all of which increasingly helped along the idea that it might not be demons doing the damage, but instead disturbances in the brain. This change of diagnosis took a very long time – a pace akin to tectonic plate shift – to catch on. Indeed, old habits die hard and throughout the 15th and 16th centuries, the uterus remained the villain and was blamed for causing the brain disturbances.

Sometime during the Enlightenment period of the 17th and 18th centuries, sorcery was finally edited out of the early medical books, and an increasingly scientific view of hysteria inserted into the text as its replacement. Gradually, hysteria was accepted to be a product of the brain, not a wayward womb, and the symptoms were regarded as bodily manifestations that came from emotional (brain-based) distress. Hysteria was a widely diagnosed form of neurotic illness among women in the 19th century. Sigmund Freud, that little rapscallion, had his own special take on it in his early works: he believed that hysteria was the result of not having completely evolved through the sexual stages of development – in other words, it was caused by firstly, the inability of women to come to terms with the fact that they didn’t have a penis, and secondly, the suppression of erotic thoughts and impulses.

Then, in the 20th century, both World War I and II turned the world upside down. Suddenly, a lot of men were experiencing symptoms of hysteria as well – a supposedly female disease. The notion of hysteria as a female affliction was finally laid to rest; the diagnosis became gender-neutral and was listed in the 1968 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders II (DSM), a book known colloquially as the Bible for psychiatric diagnoses.

However, as physicians, psychiatrists, and neurologists did further research, they found that many of the symptoms could more accurately be attributed to other mental disorders. And so, in 1980, the concept of hysterical neurosis was removed from the DSM III.

Hysteria’s colourful history is an example of how our societal and cultural standards influence our efforts to diagnose and treat people who are suffering from something that makes them “not normal”. History is littered with such examples. Take Elizabeth Packard’s experience, for instance. Her marriage to Theophilus, a Calvinist minister, had resulted in not only six children, but increasing acrimony between the two as she began to question many of his beliefs, including those on religion and slavery. This didn’t sit well with Theophilus, who was by all accounts a rather domineering man, and so in June 1860 he had her committed to the Jacksonville Insane Asylum in Illinois on the basis that she was causing “the greatest annoyances to the family” and “defying domestic control”. There she found herself in the company of other women who had been similarly institutionalised for being assertive, and for other forms of insanity including “reading books”, and “extreme jealousy”.

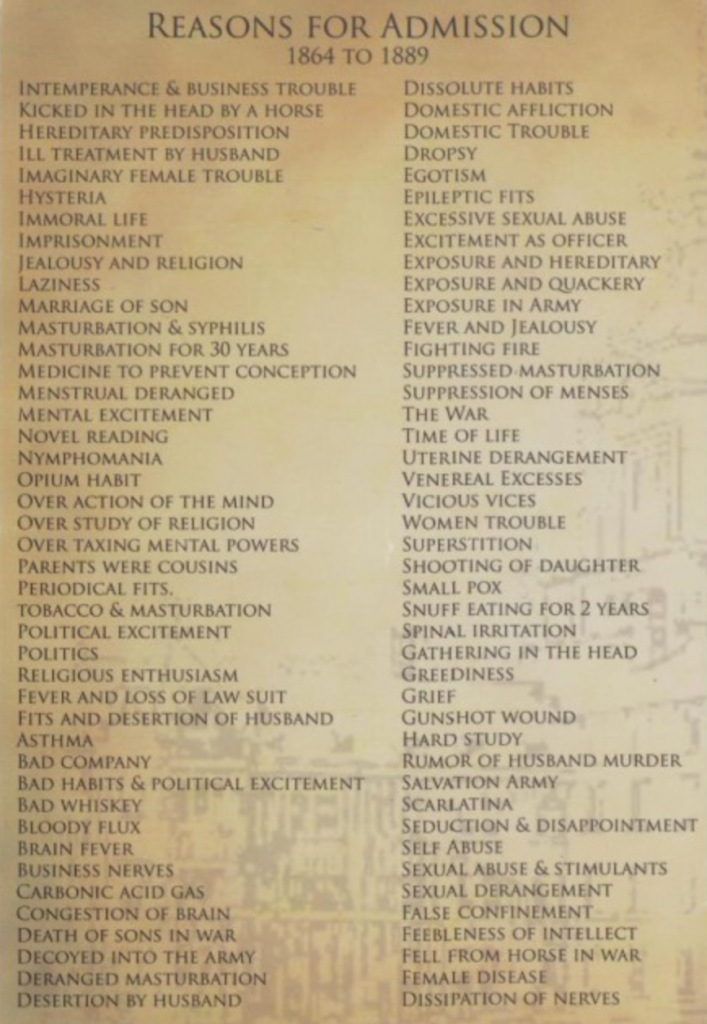

While it was commonplace in the 19th century for women to be admitted to lunatic asylums for hysteria, men were also sent off to these cruel places that were intended to sweep any evidence of mental illness under the rug from the general public. Reasons for being admitted included alleged “chronic mania”, “delusion”, “causing domestic trouble”, “overwork”, and “religious excitement”. It’s morbid fun to have a look at the list below to see if you would have qualified for admission if you were alive back then:

It’s not just slightly out-of-the-ordinary housewives that were dubbed lunatics, though. Great men and women throughout history whose ideas were out of step with the times they lived in were often called mad. Take, for example, Dr Ignaz Semmelweis (1818-1865), a Hungarian physician and scientist who became increasingly concerned with the rate at which mother and baby deaths occurred in obstetric clinics and hospitals. He noticed that mortality rates dropped when doctors washed their hands in chlorinated lime solutions before treating patients. Although he couldn’t explain why this happened (germs were only discovered later by Louis Pasteur), he nevertheless was quite outspoken that handwashing was important. His colleagues mocked him for his idea – washing your hands? They believed him to be mad. He was dismissed from the Vienna General Hospital and ostracised from the medical community, which resulted in poverty and a deterioration of his mental health. His colleagues then committed him to an asylum because of his mental state, where he would live until his death.

It was not just him, though; many of history’s most famous people were considered a bit crazy in their days:

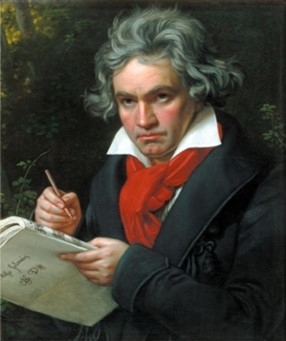

Beethoven had periods of mania during which he could compose numerous works at once, but he did his most celebrated works in his depressive periods. He had a particularly bad down period in early 1813 where he stopped caring about his appearance and would fly into rages during dinner parties. Today, his symptoms are recognised as those of bipolar disorder.

Michelangelo (1475-1564) painted the magnificent Sistine Chapel ceiling with single-minded determination and routine. He was also a maths genius. Socially, however, he was odd – he had difficulty forming relationships with people, lived in his own world, didn’t have many friends, and behaved in sometimes strange ways. Today it is believed that Michelangelo was likely on the high-functioning side of the autism spectrum.

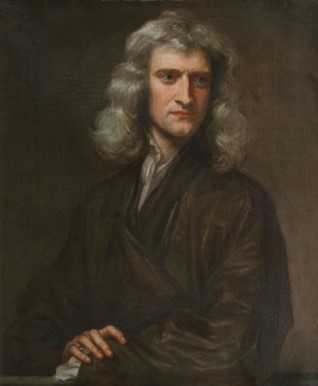

Isaac Newton (1643-1727) was arguably the greatest physicist of all time. He was a respected and prolific scientist, credited with inventing calculus, explaining gravity, and building telescopes, among many other nerdy things. He also wrote letters filled with mad delusions, experienced extreme mood swings, and had psychotic tendencies. It’s likely he suffered from bipolar, schizophrenia and was on the autism spectrum.

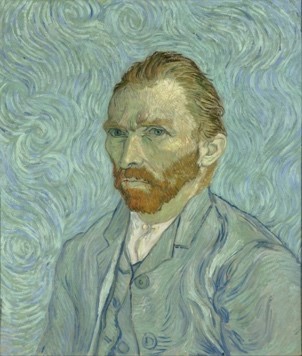

Vincent Van Gogh (1853-1890), one of the world’s most important artists, was considered a washout lunatic in his later years as he gradually developed full-blown bipolar disorder. In his words: “I put my heart and my soul into my work, and have lost my mind in the process.” In 1989, near the end of his life, he famously cut off his left ear and gifted it to a local prostitute, an act which saw the authorities arrest him and put him into a mental hospital.

An interesting thing about Van Gogh’s “madness”, is that he himself was well aware of when he was sane and when was experiencing temporary madness. But what if it’s not that easy to make this distinction, i.e., where does the boundary between insanity and normality lie?

This question intrigued Prof. Rosenham from Stanford University and so he conducted an experiment. In 1973, he recruited eight participants who had no present or past symptoms of psychiatric disorders and instructed them to admit themselves to 12 different hospitals across America. When being admitted, the participants were instructed by Rosenham to say that they had been hearing unfamiliar and often unclear voices of someone their own sex that seemed to say “empty”, “hollow”, and “thud”. In 11 instances, the pseudo-patients were admitted with a diagnosis of schizophrenia, while the remaining one was admitted with the diagnosis of manic-depressive psychosis. Once admitted, the participants stopped simulating any psychiatric symptoms.

To his consternation, Prof. Rosenham found that none of the facilities re-evaluated their diagnoses, even though all the pseudo-patients behaved normally after admission. This, he concluded, was because there is an enormous overlap in behaviours between the sane and insane!

So, a most interesting question arises – how do we know what is madness and what is sane, what is abnormal and what is normal, what is crazy and what’s merely eccentric? The answer is complicated. Firstly, increasing knowledge of how the brain works helps doctors, psychiatrists and psychologists be able to more accurately diagnose mental dysfunction. Secondly, observation of people’s behaviours can contribute to diagnosis, although this can be a bit unreliable. And then finally, as we have seen with hysteria, diagnosis is heavily influenced by the state of a society at that particular time. In the next blog post I look at the example of homosexuality to show how this happens.